A look into what I see when I listen to music.

My synesthesia is under the sound-visual variance, also known as chromesthesia. This means that whenever I hear any kind of sound, whether it is interpreted as music or not, I see a corresponding visual output in my head. Now of course, I don't see these visuals in my direct field of vision - think about it like this. If I were to ask you to picture a castle in your mind, you would probably envision a Disney or fairytale castle of some sort. Although I would probably envision the Nuremberg castle, the point here is that you can "see" a clear image that doesn't immediately exist. I am sure that you have an overarching idea of how that castle looks, but you can't see every nook and cranny of every stone and pillar in that castle in your mind unless you mentally zoom into it. My synesthesia works in quite the same way. Give me Eminem's My Name Is and I can confidently say, "I know what that song looks like." Down to the gritty texture of the bass, the crispy sharpness of each hi-hat, and Eminem's sandpaper-like nasal voice, every element has a clear form.

These attributes are the timbres that make up the textures I see from my chromesthesia. A timbre is just the way a sound sounds because of certain overtone frequencies and combinations of frequencies that result in a unique sound, allowing us to distinguish a saxophone from a clarinet, or even a sine wave from a square wave (these waves, known as pure tones, do not occur in nature by themselves and lend themselves in some shape or form in natural timbres). Each texture I see is unique to each timbre that exists - in short, I have not yet discovered the extents of my own synesthesia. When a new timbre is created or discovered by myself, my brain uses a predetermined set of rules to output the texture that results. For example, The higher a frequency, the "shinier" it looks. It also tends to look thinner, less dispersed, and much more prominent in nature, and this is probably due to the human tendency to perceive higher frequencies as louder. A bass frequency can be thought of as thick, wide, and boomy, while the mids and trebles introduces the more unique textures like muddy, grainy, slimy, or any other texture you might be able to see in real life.

Similarly, my chromesthesia also assigns colors to audio stimuli. This phenomenon is much more obscure and not as well-defined even to myself. Although I recognize the framework of how each color corresponds to a certain key, the line becomes fuzzier the more complicated the music becomes. For instance, sounds without a perceivable tone or interval are generally some combination of black, white, or grey - that is, they are purely texture. A kick drum is almost always some grey or black thud of a sound and has no real color. And since percussion sounds are usually not tuned to any particular key or frequency, most percussion has no color. But wait, you may ask, what if I tuned that kick drum to 55 Hz? Now, if you know anything about fundamental frequencies and harmonics, that is an A1 note. I am coincidentally blessed with perfect pitch, so I would probably recognize that kick drum as an A if I listened carefully enough. Suddenly, it has the potential to possess color, and that's where the problem of context arises.

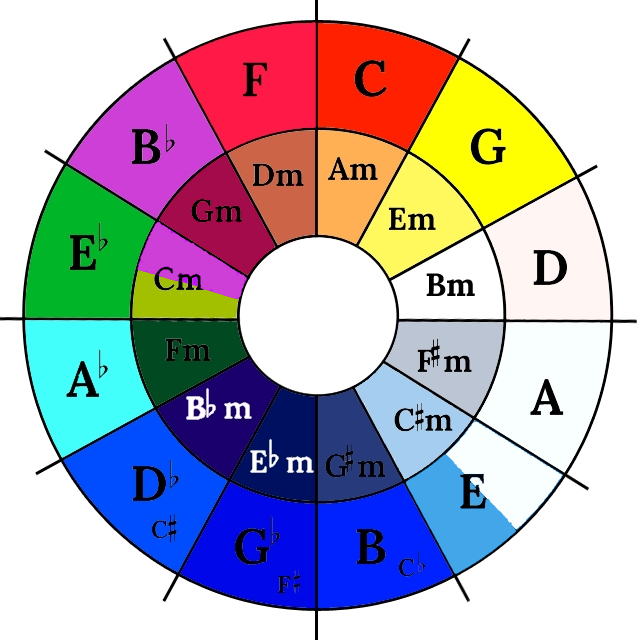

I have created a "chromesthesia circle of fifths," a crude attempt at identifying the colors that I see from each key in the 12-tone equal temperament system that the majority of music today uses, a.k.a. Western tuning.

These colors are caused at the most primitive form due to basic triads. A G flat major triad is a deep, dreamy blue, while B minor is the blankest of whites. It is important to note that these colors are only unique to me. Another synesthete may correspond individual notes to colors, or even timbres to colors rather than to keys like myself.

Why does my color wheel matter to average listeners without any ability to see the colors themselves? Essentially, it is a cheat code to analyze the complexity of chord progressions in music. A switch from E♭ major to A major is to traverse all the way to the opposite side of the circle, creating a dramatic chord change. As a result, the color shift is also drastic. On the other hand, strolling through d minor, G major, and C major doesn't require any skips on the circle of fifths, and the colors nearly blend into each other. What I just described is the classic ii-V-I progression, one of the fundamental building blocks of jazz harmony and a commonly-used progression in modern music.

Let's rewind to that A1 kick drum. Put it under a piano backing track in a minor, and the kick will take on a slightly peach hue. It is still just as nearly black, but as if someone dropped a bit of peach-colored paint into the mix. Now, change that piano to A major, d minor, or even something crunchy like c minor, and the kick will be different colors each time because of the modal context. In fact, the c minor piano would probably revert the kick back to its purely black color because the resulting chords are too crunchy to easily determine a particular color for the kick. Try interpreting this as a c minor sixth (Cm6) or part of an incomplete f minor ninth (Fm9) on the fly! Context is everything, but it also gives access to interesting palettes of color which only enhance my enjoyment of music.

There is so much more to explore with my synesthesia, whether that be new colors caused by intervals and chords outside Western tunings or the way rhythm and swing changes the spatial orientation of sounds in my head. Those are all topics for another discussion, but I am thankful for this ability that make songs just that much more complex and interesting to analyze.

- Tanay